Separate but equal education has long been unconstitutional in the U.S. Since the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case was decided in 1954, all students are guaranteed an equal chance to learn.

In reality, this is not the case.

Students of color and students with disabilities are disciplined far more often and with harsher disciplinary measures than their white peers for similar offenses. The end result of this imbalanced discipline is higher rates of suspension and expulsion for Black students and those with disabilities. According to experts, youth are at more risk to be in more frequent and more serious contact with law enforcement throughout their lives the earlier the encounters begin.

Early contact with law enforcement instead of the classroom experience starts what is known as the “school-to-prison pipeline.”

Students who are targeted for unequal discipline are removed from an educational setting and funneled into the juvenile and criminal justice system. Students who are subject to unfair and frequent discipline are more likely to drop out of high school and come into contact with law enforcement.

Many later find themselves in prison, diminishing their lifetime economic opportunities and robbing their communities of their social contributions. The effects can last for generations and only perpetuate cycles in poverty and inequality.

Missouri is one of the school-to-prison pipeline’s worst contributors.

In our October 2017 report, “From School to Prison: Missouri's Pipeline of Injustice,” we reported that Black students are more likely to receive suspensions than White students. This summer, we took a look at the newest data and learned that things have only become worse. Black students are now five times more likely to be suspended than White students overall. Black preschoolers are more than four times as likely to be suspended compared to White preschoolers -- Missouri gives multiple out-of-school suspensions to Black preschoolers than in 44 other states.

The effects of this pipeline have both a human cost and a financial cost.

We will explore the real consequences of the school-to-prison pipeline by following two Missouri students: one, who finishes his education and builds a successful career, and another, who is expelled from school and finds herself in prison.

It Starts in School

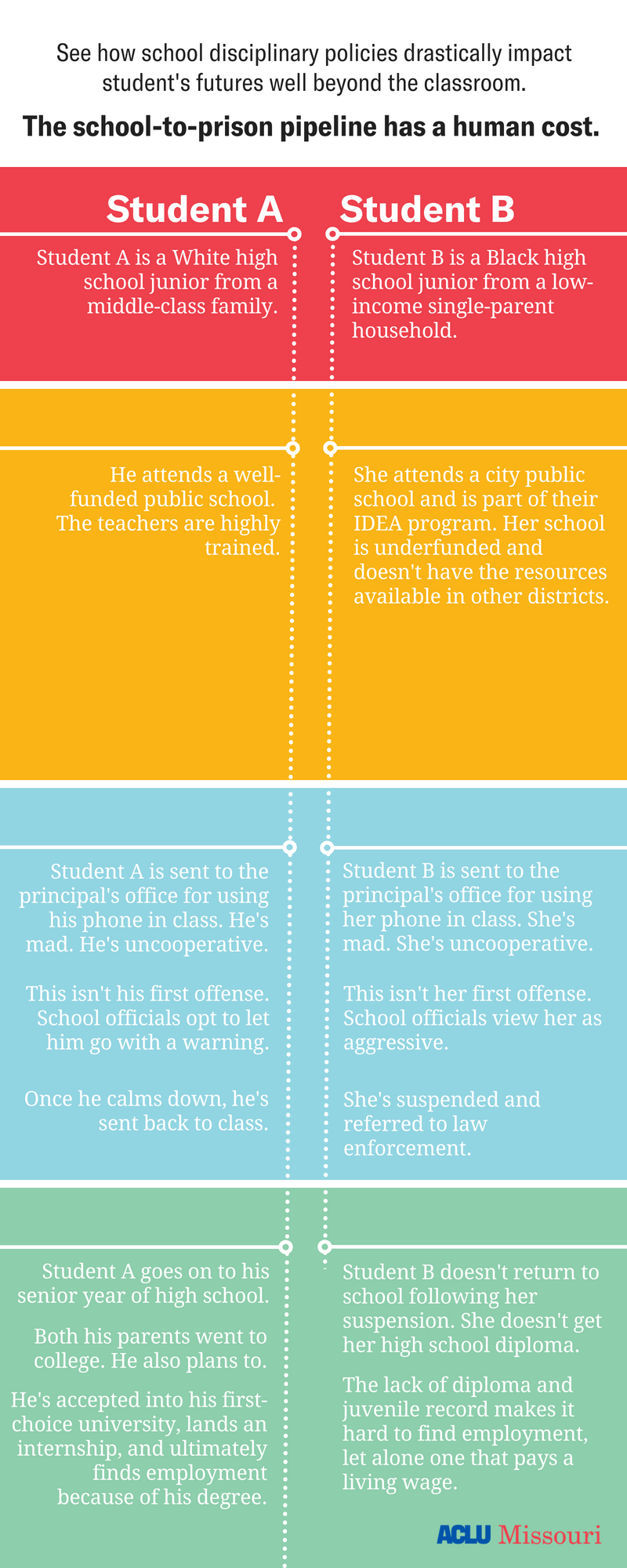

Student A is a White, 11th grader from a middle-class family. Both of his parents have college degrees. Student A plans on attending college, too.

Student A attends high school in one of Missouri’s top public school districts that is well-funded and has highly trained teachers. In 2012, Missouri spent 17 percent more per-pupil on its wealthiest school districts, behind only Pennsylvania and Vermont for the largest per-pupil spending gap in the U.S.

Student A has lots of one-on-one time with his teachers and has access to resources, including quality textbooks, counselors and technology.

Student B is a Black 11th grader from a low-income, single-parent household. She is also an Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) student, meaning her school is legally required to provide services that meet her needs.

Student B’s mother didn’t complete college and her father never enrolled. A college degree typically comes with a higher expected lifetime earning potential, but if a child’s parent didn’t attend college, the chances become lower that the child will have that opportunity.

Student B plans on working immediately after graduating high school. Life is expensive.

Student B’s school district is one of the poorest in Missouri. It lacks a majority of the resources available in Student A’s district.

Without realizing it, many of Student B’s teachers are likely to hold implicit bias against black students. Recent studies show the “adultification” of black students, especially girls, is rampant. Black children are perceived as more knowledgeable than white students about adult topics. Even more damaging, these studies illustrate that Black girls are viewed as more self-sufficient and less likely to receive the guidance and nurturing that is critical for child development.

Such false perceptions are the foundations for the school-to-prison pipeline, and they create the first noticeable discrepancies between the two students’ disciplinary experiences.

For example, Student B has received multiple verbal warnings for using her cell phone during class. Halfway through her junior year, Student B is sent to the principal’s office for refusing to put her phone away. She begins to protest, which her teacher perceives as aggressive behavior. Now viewed as a threat to school safety, Student B is suspended and referred to law enforcement. She ultimately does not return to school, instead spending the next year and a half in an alternative school and dropping out just shy of receiving her diploma. Her plans to graduate and get a job are indefinitely put on hold.

On the other hand, Student A is also prone to using his cell phone in class. As the “class clown,” he is known for belligerent behavior and often talks back to his teachers. Yet when Student A is sent to the principal’s office, he receives a stern warning and is sent back to class. Student A finishes high school without any law enforcement interactions. He is accepted to an accredited university and begins planning the next steps in his educational career.

These outcomes are no joke. For many Black students, they are simply reality.

According to a study by Georgetown University, Black girls like Student B are two times more likely than White students to be disciplined for minor infractions, such as using a cell phone in class or loitering in the hallway. Although they are just 8 percent of enrolled students, Black girls make up 13 percent of suspended students. Research also shows that suspended students are likely to be arrested on the day of their suspension.

The ACLU’s school-to-prison pipeline report further corroborates this trend. As a black girl in Missouri, Student B is 2.5 times more likely than Student A to be disciplined for “disobedience” and three times more likely than Student A to be disciplined for “disruptive behavior.” As an IDEA student, she is three times more likely to be suspended and twice as likely to receive corporal punishment.

The result is clear. While Student A walks down the aisle on graduation day, Student B sits in a juvenile detention center. She has been unfairly removed from her peers, and from opportunities she cannot get back.

The Lifelong Effects of Prison

Student B’s prior interactions with law enforcement have already set her on a different path than Student A. When she ages out of the juvenile justice system, Student B could face the next phase of the pipeline: adult prison.

According to the National Institute of Justice, more than half of juvenile offenders continue to offend until age 25. If Student B follows this trend, she will become part of the overwhelmingly Black prison population. The ratio of black to white prisoners in Missouri is 4 to 1, according to The Sentencing Project.

If she is imprisoned for the average of 6.5 years in Missouri, her incarceration will cost taxpayers at least $22,187 per year, totaling $144,215.

However, the same study shows that only 16 to 19 percent of juvenile offenders continue to offend after age 25. After spending much of her youth in the system, Student B is finally released and ready to rejoin society. Yet Student B’s lack of education and prior convictions will bar her from many jobs.

Student B is at a major economic disadvantage, despite her desire to work. Without a high school diploma, her lifetime earnings will total only $973,000. In the end, Student B has less of a chance at a quality life where she can contribute fully to her community and the economy.

Life is radically different for Student A. After graduating college with a bachelor’s degree, he can expect to earn $2,268,000 in lifetime earnings. This number is even higher should he choose to pursue a master’s or doctoral degree.

Student A has a much larger pool of opportunities available to him because he was able to complete his education and has no criminal record.

The True Cost

Clearly, our two students’ divergent experiences caused them to live very different lives.

Yet the cost of the school-to-prison pipeline is not just a social one. Locking up minority students and robbing them of their future is expensive, and taxpayers are footing the bill.

How You Can Help

Unquestionably, the school-to-prison pipeline has put an enormous social and financial burden on our country. For far too long, many Americans have been pushed to the margins without any hope of achieving the American Dream.

It is time to end structural inequality and provide all children with an equal education as guaranteed by the Constitution.

We can put an end to the school-to-prison pipeline through the following actions:

- Build a positive school environment that encourages and affirms students

- Implement new discipline guidelines that focus on keeping students in school

- More implicit bias training for school resource officers and police who deal with students

- Increase resources and funding for underprivileged school districts

Sign our petition and pledge to end the school-to-prison pipeline in your community.

By recognizing disparities in discipline and taking action, we can make sure all Missourians have an opportunity for an education. Justice doesn’t stop at the schoolhouse door.